-40%

Ancient Roman Empire 2 Coins COMMODUS and ANTONINUS PIUS Silver Denarii

$ 39.07

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

. style="text-decoration:none" href="https://emporium.auctiva.com/timelessthing" target="_blank">. href="https://emporium.auctiva.com/timelessthing" target="_blank">timelessthing Store

. href="https://www.auctiva.com/?how=scLnk1" target="_blank">

ROMAN EMPIRE

2 Ancient Coins

Silver Denarii

Of

COMMODUS

Marcus Aurelius Commodus

Roman Emperor: 180-192 AD

Obv: M COMM ANT P FEL AVG BRIT PP

Laureate

bust of Commodus right

Rev: MIN VICT PM TR P XIIII COS V DES VI

Minerva standing left holding Victory and spear, shield and trophy nearby

17.00 mm

ANTONINUS PIUS

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Pius

Roman Emperor 138-161AD

Obv: ANTONINVS AVG PIVS PP TR P XI

Laureate bust of Antoninus Pius right

Rev: COS IIII

Annona standing left holding corn ears and anchor, modius with corn ears left

17.00 mm

PRIVATE

ANCIENT COINS COLLECTION

SOUTH FLORIDA ESTATE SALE

( Please, check out other ancient coins we have available for sale. We are offering 1000+ ancient coins collection)

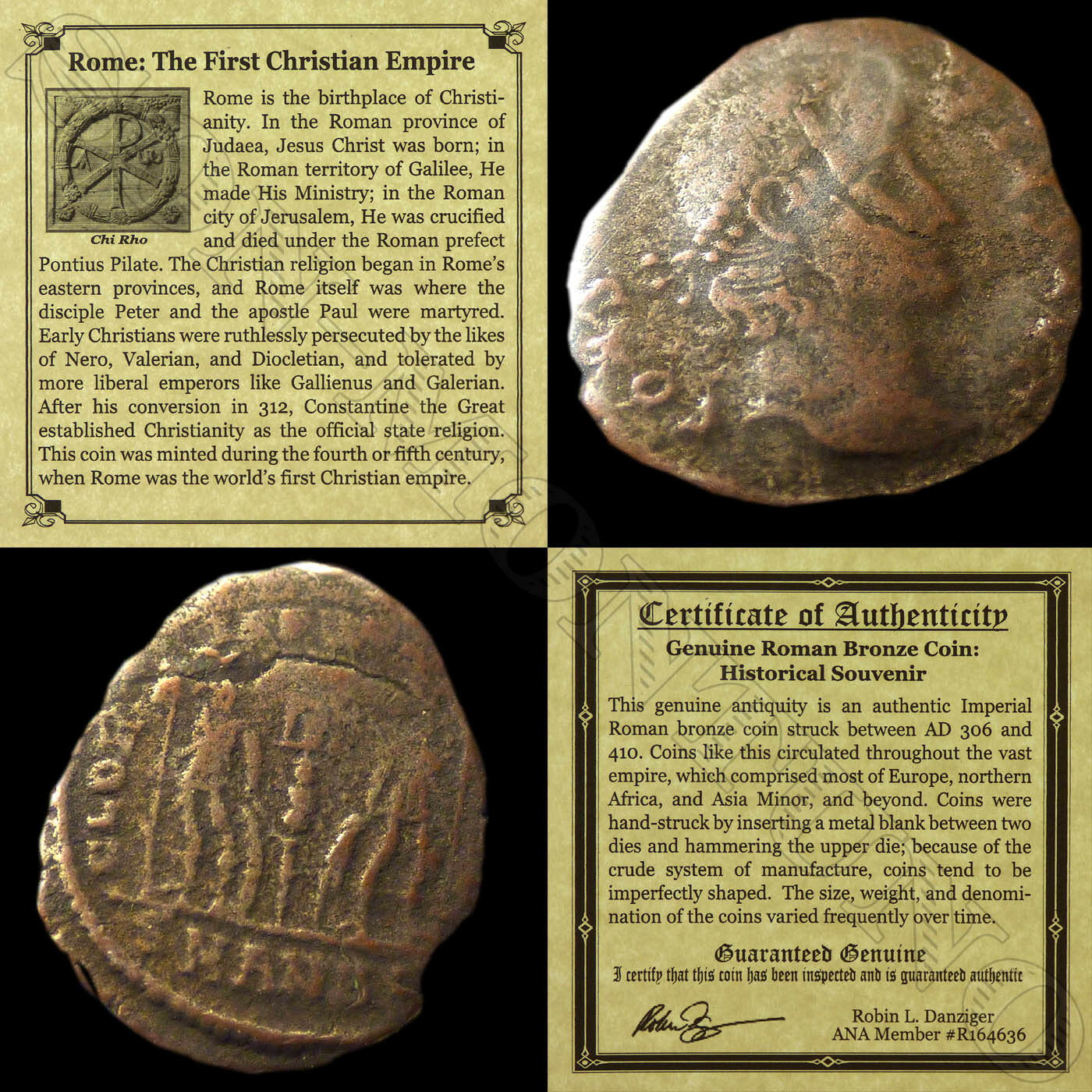

ALL COINS ARE GENUINE

LIFETIME GUARANTEE

AND PROFESSIONALLY ATTRIBUTED

The attribution label is printed on archival museum quality paper

An interesting lot of 2 silver coins of two Roman Emperors,- Antoninus Pius and Commodus. The coins come with display cases, stands and attribution labels attached as pictured.

The attribution label is printed on archival museum quality paper.

A great way to display an ancient coins collection. You are welcome to ask any questions prior buying or bidding. We can ship it anywhere within continental U.S. for a flat rate of 8.90$. It includes shipping, delivery confirmation and packaging material.

Limited Time Offer:

FREE SHIPPING

(only within the continental U.S.)

The residents of HI/AK/U.S. Territories and International bidders/buyers must contact us for the shipping quote before bidding/buying

Commodus

Commodus was born on 31 August AD 161 at Lanuvium, roughly 14 miles south-east of Rome.

Of the fourteen children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina the Younger, Commodus was the tenth. He was born one of twins, though his twin brother died when he was only four years old. He was given the name Commodus in honour of Marcus Aurelius' co-emperor, who had originally borne it.

Commodus was in fact the only son of the royal couple to survive childhood.

From an early age Commodus was groomed to succeed his father to the throne. Already at the age of five, in the year AD 166, he was made Caesar (junior emperor). And in AD 177, after the revolt of Cassius, Marcus Aurelius made him Augustus and thereby joint emperor. Commodus indeed led the troops in the wars on the Danube together with his father from AD 178, until the death of Marcus Aurelius in AD 180.

Had Commodus been emperor from AD 177, no-one doubted that true power remained in the hands of his father. And so his reign is generally seen to have begun on the death of his father in AD 180.

By all accounts Commodus was a handsome man, with curly blonde hair. But he appeared to possess a weak character and was easily influenced by others. But so too was he prone to cruelty and excessive behaviour. To an extent his behaviour was still held in check, when his father was still alive, although then too some believed to detect the signs of a new Nero in the young heir. Cassius' earlier rebellion, when he mistakenly thought Marcus Aurelius had died, might well have been inspired by a fear of what was to come if Commodus came to the throne.

Commodus' accession to power, ended a spell of 80 years in Roman history which had brought men to the throne by merit rather than by birth. The last man to take the throne merely by right of birth had been Domitian.

If Commodus merely had not lived up to the gruelingly high standards of his father, the world would have most likely forgiven him. But rather than just failing to be a brilliant emperor, Commodus was in fact a terrible one. Cruelty, vanity, power and fear formed into a terrifyingly dangerous mix of bloodlust, suspicion and megalomania. Commodus should be remembered as a monster, a tyrant who renamed months in his own honour, and who slaughtered his way through the circuses in ludicrous displays of 'manliness'.

Despite his initial promises to the army to continue Marcus Aurelius' attempts of expanding the empire into the territories conquered from the Quadi and Marcomanni, Commodus soon after surrendered all his father had achieved in his wars.

Indeed, Commodus' thoughts that to annex these new territories might have been beyond the capabilities of Rome, could well have been correct. And had emperor Hadrian not relinquished some of the gains of his predecessor Trajan ? But Commodus was no Hadrian and the army knew it. Commodus' retreat from those so direly contested territories was understood as an utter betrayal of everything the beloved Marcus Aurelius had stood for.

Whatever the circumstances surrounding the Roman withdrawal, Commodus did make a treaty with the Marcomanni. The treaty proved very successful in pacifying the barbarians, forcing them to accept various conditions. Although such peace might also have been due to Marcus Aurelius' late successes having reduced the barbarians' capacities for war.

With peace re-established on the Danube, Commodus returned to Rome. It wasn't long before he uncovered the first conspiracy against him. In AD 182 his own sister Annia Lucilla, together with her cousin, the former consul Marcus Ummidius Quadratus, were involved in a plot to assassinate him.

Lucilla's second husband Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus of Antioch, who had held the office of consul twice and who was a possible rival to the throne, was whom the plotters sought to make emperor.

And it was Pompeianus' nephew Quintianus who burst from his place of hiding with a dagger, trying to stab Commodus. But the guards were faster than Quintianus. He was overpowered and disarmed without doing the emperor any harm.

Quadratus and Quintianus were executed. Meanwhile the emperor's sister Lucilla was first banished to Caprae but was soon afterwards put to death anyhow.

Not much later the praetorian prefect Tarrutenius Paternus was also executed, either for being part of the plot to kill Commodus, or for being a conspirator in the murder of the emperor's influential court chamberlain from Bithynia called Saoterus (it might have been Saoterus' advice which caused Commodus to withdraw from the territories his father had conquered beyond the Danube).

With the prefect Tarrutenius Paternus killed, the other remaining prefect, Tigidius Perennis, was left in sole charge of running the empire on the emperor's behalf, for Commodus took little interest in the day-to-day running of government.

Perhaps since the notorious prefect Sejanus during Tiberius' reign, no praetorian commander had held so much power.

With Perennis in charge of running the empire, Commodus' life became one long party. Entertaining a harem of, so it is said, 300 girls and women and 300 boys, some of which might have been kidnapped, he indulged in lengthy orgies and revelled in decadent luxuries.

But with his hands on all the levers of power it was only a matter of time before Perennis himself was seen as too powerful by Commodus. Rumours that he was planning to rid himself of the emperor to rule on his own were further backed up by the fact that he made two of his own sons governors of the important Danubian military province of Pannonia.

Though in AD 185, Perennis had been in power for three years, a delegation of 1500 disgruntled soldiers from the British legions arrived in Rome and warned Commodus of a plot by Perennis.

If the praetorian prefect had really plotted against his emperor's life remains unclear. But what is known is that Perennis had brutally crushed a mutiny in Britain, which will have won him no favours with the army based there.

Whatever the true reasons, Perennis was killed by his own praetorians. So too his wife, his sister and his sons were all executed.

The man believed to have organised these executions on Commodus' behalf was Marcus Aurelius Cleander, a freedman having once been brought to Rome as a Phrygian slave. Cleander now was placed in the vacant position of praetorian prefect and became not merely Commodus' closest advisor, but began to run government on the emperor's behalf as Perennis had done. As head of the emperor's security, he was given the title pugione ('the Dagger') by Commodus.

If there had been talk of corruption by Perennis, then Cleander achieved true notoriety by his greed. His might well have been the most corrupt government ever to have ruled the Roman empire.

Public offices were sold to the highest bidder, one year actually seeing no less than 25 consuls inaugurated. Cleander kept a lot of this money for himself, but took care to share these revenues with his emperor.

But, just as Cleander had helped bring down Perennis, then so did he fall. Papyrius Dionysius, the prefect of the grain supply to Rome (praefectus annonae) managed to engineer a food shortage in Rome and blamed it on Cleander. In AD 190 the garrison of Rome, accompanied by an angry mob, sought out Perennis and killed him. Commodus did nothing to save the head of his government.

In the later stages of his reign Commodus became ever more obsessed with performing as a gladiator. He even changed parts of his palace into an arena in order to fight beasts there or gladiators. But Commodus was not satisfied with such private fights. He also appeared in public as a gladiator. For the Roman public, or at least the privileged classes, it was a harsh shock to see their emperor publicly debase himself to the level of a slave or a prostitute in the arena. For, in Roman attitudes, gladiators were indeed understood as one of the lowest possible levels of society.

But Commodus cared little about such attitudes. He liked to appear in the arena dressed up in a lion skin as the ancient hero Hercules, son of Jupiter. There is little doubt that by this time Commodus was deranged. Senators had to be present at such performances, as their emperor slaughtered helpless animals or hapless gladiators. At one day he is said to have killed one hundred bears. Given this number, it is hard to imagine that the animals were anything but helplessly tethered with no chance to fight back and were simply stabbed to death. The fighters who would meet Commodus in the arena stood equally little chance. For if the emperor was armed, all they would have were harmless wooden weapons.

Cruel as this no doubt was, Commodus also seemed ridiculous to many. Was gladiatorial combat also concerned with grace as well as skill, the emperor apparently possessed little of it. Many spectators are said to have struggled not to laugh out loud at the sight of such ridiculous displays.

Inscribed on the base of one statue of his was that he had slain twelve thousand men. If this is true or not cannot be said. But it says much about the man to boast of such 'achievements'.

If Commodus sought to be Rome's hero in the arena, if he even had the nobles ordered to call out prescripted compliments from the tiers, he also was jealous of any other gladiator's fame.

In one case, on hearing that a bestiarius (animal fighter) called Julius Alexander had on horseback killed a lion with a javelin, he had him executed.

As if this all wasn't enough, Commodus decided that, in accordance to his divine talent, Romans should pay to see the prowess of the 'Roman Hercules' in the arena. And so he demanded to be paid one million sesterces from the gladiatorial fund for every appearance.

Only chariot racing was something Commodus would not do in public. This stigma he sought to avoid. Although the historian Dio Cassius mentions that indeed he did so on some nights, when he might not be seen by the public. If he did so by day, Commodus made sure to do so out of sight. But, even on these occasions, he made sure to wear the livery of the popular 'Green' racing faction.

Whilst the emperor was playing gladiator in Rome, the empire itself was facing hard times. The army was viewed with suspicion by a population which knew more and more spies and military secret police at work.

Had the emperor nearly bankrupted the imperial treasury with his expensive lifestyle, then he simply replenished it by accusing senators of treason and having their property seized.

But things were to get even worse. Had in AD 191 a fire destroyed some of the centre of Rome, then Commodus had it rebuilt. But, wanting to claim the credit for the 'rebuilding of Rome' he decided to rename the city altogether. Colonia Commodiana was to be its new name (City of Commodus).

So too, the army should henceforth be the Commodian army, and even the ancient institution of the Roman senate was to bear his name in future.

Then, in November AD 192, plans emerged that to celebrate the 'new' city, Commodus was to take office as consul on 1 January AD 193. He even intended to march to the senate from a gladiatorial school within the city - dressed as a gladiator.

It appears to have been the praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus who decided it was time to act against the madman on the throne.

Carefully a plot was crafted against the emperor. The court chamberlain Eclectus and the emperor's favourite concubine Marcia added their support to the undertaking. Quietly people who supported the plot were placed into key positions. Septimius Severus and Clodius Albinus, African allies of Laetus, were given the governorships of Upper Pannonia and Britain. Pescennius Niger, another friend of Laetus, was put in charge of Syria. As the future emperor the conspirators agreed on Publius Hevlius Pertinax, the city prefect of Rome.

The initial plan appeared to be that Marcia should poison him on the evening of 31 December AD 192. But Commodus merely became nauseous and vomited, ridding himself unwittingly of the poison.

But the plotters appeared to have a back-up plan in place. An athlete called Narcissus, who was employed as Commodus' wrestling partner, overpowered and strangled Commodus in his bed on the same night.

If Laetus had been the chief conspirator against Commodus, then he did save his body from being disgraced by carrying it away and giving it a secret burial outside Rome. The precaution proved worthwhile, for the senate now vented its anger on the tyrant, having his name removed from all records and destroying his statues.

Though in a strange twist of fate, the new emperor Pertinax should have Commodus' body exhumed and laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Septimius Severus even had Commodus deified in AD 197.

Antoninus Pius

Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionus Arrius Antoninus was born on 19 September AD 86 at Lanuvium (ca. 20 miles south of Rome). His family had long before come from the city of Nemausus (Nïmes) in southern Gaul, but for a long time since they had been a prominent and distinguished family at Rome.

Antoninus' father, Titus Aurelius Fulvus, had held the office of consul once in AD 89, his grandfather had even held it twice.

As a boy Antoninus grew up at the family estate at Lorium in southern Etruria, roughly 10 miles to the west of Rome. He was raised first by his paternal grandfather, as his father died when he was still young. On the death of this grandfather, the maternal grandfather took charge of him.

Inheriting the walth of both his grandfathers made Antoninus one of the richest men in Rome.

He embarked on the traditional career for a senator, climbing the ladder of various offices, achieving the post of quaestor, then praetor and, alas, in AD 120 becoming consul under emperor Hadrian.

After this Hadrian chose him to be one of the four high judges who administered administered law in Italy.

Next he served as governor of the province of Asia, from AD 135 to 136.

Most likely on the basis of the very good reputation he had made for himself as governor of Asia, Antoninus, when he returned to Rome was made a member of the imperial council, a body of advisors to the emperor.

Despite his consulship and remarkable conduct as governor of Asia, Antoninus' experience of government was fairly limited. More still he possessed no knowledge of any military matters whatsoever and, other than his stay in the province of Asia, he had never been beyond the borders of Italy.

So it was clearly his impressive person - honourable, sound and clearheaded - which won him the respect of the senate and the emperor.

Then, on his 62nd birthday (24 January AD 138) Hadrian, by now of failing health, announced he was to adopt Antoninus Pius. The adoption ceremony was held a month after, on 25 February AD 138. The ceremony revealed Hadrian's plans for the empire. In adopting Antoninus, Hadrian just sought a safe pair of hands into which to trust the empire for the immediate future. But 51 years old at the time and childless, Antoninus was not to be the main aim of Hadrian's intentions.

For the ceremony in which Hadrian adopted Antoninus, simultaeously had Antoninus adopt Marcus Annius Verus (Marcus Aurelius), Hadrian's young nephew, and Lucius Ceionius Commodus, young son of the deceased Lucius Ceionius Commodus, who had been Hadrian's first choice as heir.

If however Hadrian had thought that the relatively old Antoninus Pius would not reign for long before his death would hand power to the heirs he intended then he was wrong. For Antoninus was to live to the ripe old age of 74 (almost as old as Augustus), ruling longer than Trajan or Hadrian.

Following the example of Hadrian, Antoninus was also a bearded emperor.

Tall and handsome, physically strong, he possessed a calm and kind nature, though with a stern, aristocratic air.

He represented many of the virtues Roman sought in their emperor. An accomplished speaker, sound in morals, incorruptible by the temptations of easy living, not given to flaunt his wealth, he was dedicated to his duties.

Compared to his predecessors Antoninus was clearly not an ambitious emperor. But then he most likely understood himself as the custodian of an empire which was to be passed on to the young heirs chosen by Hadrian. And so he sought to maintain, rather than to make his own mark.

But there is no doubt that Antoninus possessed a willful, even determined side. For when he began to bend with old age, he wore a truss made of splints of lime wood, to allow him to walk erect. For evidently it was his decision that Romans should have an emperor who should walk upright.

Antoninus had no surviving sons. His only surviving daughter Faustina the younger eventually married Marcus Aurelius, further strengthening the succession intended by Hadrian.

The reason for the addition 'Pius' (meaning 'dutiful' or 'respectful') to his name is something which appears unclear even to the Roman historians. Several difference possibilities are known;

- he used to support his frail and elderly father-in-law with his arm when attentning the senate

- he pardonned those whom Hadrian embittered by ill-health had sentenced to death

- he insisted on great honours being bestowed on Hadrian, despite general opposition

- he guarded Hadrian agaisnt killing himself when the emperor despaired at his illness

- he was a truly compassionate and kind emperor who ruled with great care and moderation

At the death of Hadrian on 10 July AD 138, Antoninus' succession to the throne was a seemless, peaceful event. Ther ewas no opposition. The officials of Hadrian's government remained largely unchanged. Antoninus, if already respected before his accession, quickly won the goodwill of the senators, for being a moderate ruler, who was respectful of the ancient institution of the senate.

However, all should not go smoothly at first. Namely the deification of Hadrian which Antoninus demanded, was vehemently opposed. Hadrian had been unpopular, even hated. Worse still he had executed some senators.

But it was to be a battle of wills which Antoninus won. He clearly understood it as his duty to have divine status conferred upon the man, - his adoptive father ! - to whom he owed the throne. To have failed in this duty would not only have questioned the honour of Hadrian, but so too that of Antoninus himself.

And so, even if deeply unpopular and bitterly opposed by the senate at that early time of his reign, Antoninus' reasons were still much understood and respected.

These initial problems behind him, Antoninus won renown for being a mild and compassionate ruler. He established new laws, protecting slaves from cruelty and abuse. During his reign two treason trials were conducted, yet not, like in previous reigns, blindly following the whims and allegations of an emperor, but according to law. Also Antoninus avoided any witch-hunts to find co-conspirators.

As a consequence to such a style of rule, Antoninus was a popular emperor.

Antoninus did not travel the empire like his predecessor, in fact he hardly ever left the capital at all during his 23-year rule. And if he left he would never move much further away from Rome than Campania or Etruria. He said, he worried for the expenses an emperor and his court might incur upon a province, if he chose to travel.

If Antoninus' reign is much known for its peace and tranqulity, it is due to the calm of the man, rather than due to there being true peace along the borders of he empire.

Southern Scotland was conquered, with Hadrian's wall being abandoned and a new defence - the Antonine Wall - being built ca. 40 miles further north.

Brigands caused trouble in Mauretania (AD 150), next trouble arose in Germany, an uprising took place in Egypt (AD 154), rebellions flared up in Judaea and Greece. Another rebellion arose in Dacia (AD 158) and conflicts ensued with the Alans.

But Antoninus was at times able to convince an opponent of the futility of war, merely by threatening it. Knowing of the renown of the Roman legions, he sent a letter to the king of Parthia, Vologaeses telling him of Rome's willingness to intervene should he decide to attack Armenia. Vologaeses thougt better of it and dropped his plans for an attack.

Alas, Antoninus died after a very short illness in his sleep, having handed the reins of government to his adopted son Marcus Aurelius on that very day, 7 March AD 161.

Antoninus, died a very popular man and was deified by the senate without opposition.

His body was laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian, together with the body of his wife and sons, who had died much earlier.

Antoninus' famous successor Marcus Aurelius paid this tribute to him: 'Remember his qualities, so that when your last hour comes your conscience may be as clear as his.

SHIPPING INFO:

- The Shipping Charge is a flat rate and it includes postage, delivery confirmation, insurance up to the value (if specified), shipping box (from 0.99$ to 5.99$ depends on a size) and packaging material (bubble wrap, wrapping paper, foam if needed)

- We can ship this item to all continental states. Please, contact us for shipping charges to Hawaii and Alaska.

- We can make special delivery arrangements to Canada, Australia and Western Europe.

- USPS (United States Postal Service) is the courier used for ALL shipping.

- Delivery confirmation is included in all U.S. shipping charges. (No Exceptions)

CONTACT/PAYMENT INFO:

- We will reply to questions & comments as quickly as we possibly can, usually within a day.

- Please ask any questions prior to placing bids.

- Acceptable form of payment is PayPal

REFUND INFO:

- All items we list are guaranteed authentic or your money back.

- Please note that slight variations in color are to be expected due to camera, computer screen and color

pixels and is not a qualification for refund.

- Shipping fees are not refunded.

FEEDBACK INFO:

- Feedback is a critical issue to both buyers and sellers on eBay.

- If you have a problem with your item please refrain from leaving negative or neutral feedback until you have made contact and given a fair chance to rectify the situation.

- As always, every effort is made to ensure that your shopping experience meets or exceeds your expectations.

- Feedback is an important aspect of eBay. Your positive feedback is greatly appreciated!

. style="text-decoration:none" href="https://mostpopular.sellathon.com/?id=AC1019108">